When you’re a writer, there are bad days and good days. Some days, you sit and write, and the words feel like they’re in someone else’s head; and some days, you write and the writing is fast and right, and you think that each word is a gift from some muse that really and completely loves and cares for you and what you have to say.

That’s the way it is for all of us, I think, but one of the things that I’ve come to feel about writing on bad days as well as good ones is that the progress, the movement forward, the work, is all important. It doesn’t matter finally if the writing I’m doing is going bad or going good, just so long as I keep writing. Putting one word after another, the bad days will give way to good days because writing is an incremental art. One word after another, and another word after that.

This word-by-word idea came to me from listening to the painter Chuck Close do an interview with Terry Gross on “Fresh Air” a couple years ago. I was just starting to write my first novel Suitcase Charlie then; I had finished the first chapter, and I was looking at the tall hill of the second chapter, and the long row of hills and mountains beyond that. Finishing that novel seemed impossible. I had been writing poems for the last thirty-five years and was comfortable working with poems. Unlike novels, they live in little spaces, valleys and small plots of earth. I hadn’t written fiction of any kind since I was in college 35 years ago, and I was sure I couldn’t move beyond that first chapter.

Then I heard that Chuck Close interview.

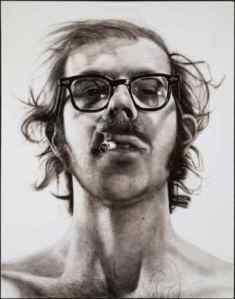

I love his portraits, his giant canvases, 15 and 20 feet high and almost as wide. They’re a human marvel. Terry asked him how he manages to create those mountains of paintings, and he said something that stopped me. He said that painting was an incremental art, one dot of paint and then another.

I had seen his paintings close up years ago at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Chicago, and I knew just what he meant. If you look at those giant canvases what you see is that each one is made up of thousands and maybe hundreds of thousands of little dabs of paint, each dab almost a perfect moment of painting in itself. A little Jackson Pollock dab of painting — one right next to another and another and another.

And I started thinking of my novel that way, each word, each line, each paragraph. One dab of words after another.

I knew I could write a word–it wasn’t daunting to do that. And I knew I could write a line. And I figured I could keep going and going, one word after another after another.

And I did.

I finished my first novel and it came to 98,643 words, and all of them are on a literary agent’s desk right now, and then I finished the second novel.

And while I’m revising it, I’m starting work on my third . I’m on word 236 and climbing.

Like the poet Rilke says, “Patience is everything.”

________________________________

My novel Suitcase Charlie is available at Amazon as a Kindle or a paperback. Just click HERE.

You can hear a podcast of Terry Gross’s interview with Chuck Close: podcast.

Here’s a link to Chuck Close’s website: click.

The copyrighted painting of Close is from a site about his various self-portraits.

.jpg&container=blogger&gadget=a&rewriteMime=image%2F*)